Maps In The Stars: How Polynesians Used Celestial Navigation To Become The Best Explorers In The World

Here's a question for all of our diehard history and geography buffs out there: What do modern-day Russia, Colonial Spain, the British Empire, the Mongol Empire, and Polynesia all have in common?

At one point in history they could all be considered as the largest nation on Earth.

Though Polynesia today is a conglomerate of nations that were independently colonized, the boundaries of the original Polynesian nation stretched from Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the southwestern corner, to the Hawaiian Islands in the north, and all the way out to Rapa Nui (Easter Island) off the South American coast.

In total, the Polynesian Triangle spans 6 million square miles of open ocean and islands—and when viewed ethnically as opposed to politically—can still be considered as one the largest countries found on Earth today.

Where Did Polynesians First Come From?

The answer to that question is one of historians' greatest ongoing debates.

The leading theory is that Polynesian ancestors started in Southeast Asia, and over the course of thousands of years, constructed vessels and used currents to populate offshore islands. As their skills in wayfaring and navigation grew, the Polynesians sailed their double-hulled canoes for thousands of miles to the east.

While the timing of the Pacific migration is disputed, it's believed Polynesians reached Samoa and Tonga as early as 1200 BC.

From there they fanned out to the Marquesas Islands as early as 300 AD, eventually heading north to the Hawaiian Islands between 400 and 600 AD. It's believed that Tahiti and Easter Island were settled about the same time, and later on—around 1200 AD—the Polynesians voyaged southwest to the islands of Aotearoa.

Other theories suggest that the Polynesians may have actually sailed from South America. One of the main proponents of this alternative theory was the Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl, who, in 1947, famously sailed aboard the Kon-Tiki from the coast of Peru to the Tuamotu Islands—over 4,300 miles away.

More than just the Kon-Tiki, however, sweet potatoes and chicken bones demonstrate a link between Polynesians and South America. Known as 'uala here in Hawaii and kumara down in New Zealand, the sweet potato is a staple crop of ancient Polynesian cultures.

That said, it's actually a crop that's native to the Americas as opposed to Polynesia, and its origins have been traced to early cultures in the area of modern day Ecuador.

Another link is in chicken bones that were found in South America, where carbon dating has traced them back to around 1350 AD.

Before the finding of the chicken bones, it was widely believed that chickens were introduced during the days of Spanish conquest, although considering that the bones match the DNA of Polynesian breeds of chicken, it's simply more evidence that Polynesians had a connection with the South American continent.

So, while the sweet potato and chicken bones might lend credence to Heyerdahl's theory, the more likely scenario is that Polynesians voyaged all the way to South America—trading chickens from their voyaging canoes for crops of the purple potatoes.

Either way, the fact that these islanders could successfully navigate across the Pacific Ocean, hundreds of years before "modern" cultures would even "discover" America, is reason enough to consider Polynesians the greatest navigators on Earth.

Celestial Navigation and Wayfinding

Perhaps what's more fascinating than the journeys themselves, is just how the Polynesians got there.

When sailing out on the open seas in their dugout voyaging canoes, Polynesians would navigate by using the stars and all of the elements around them. In addition to following the path of the stars, navigators would use the currents and wave patterns to determine their direction and heading.

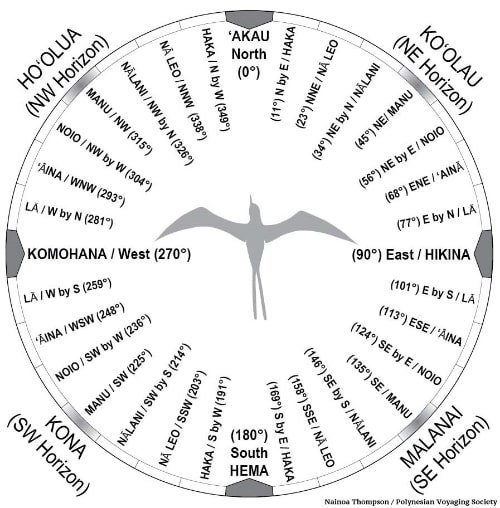

In this star compass created by Nainoa Thompson—master celestial navigator—you can see how Polynesians subdivided the sky into corresponding quadrants. When a star rises at a specific point on the horizon, it will ultimately set in the opposite quadrant from where it originally rose.

Take, for example, the sun rising in hikina (the east). When sailing out in the middle of the ocean, a navigator can tell at every sunrise which direction is east.

Similarly, at every sunset, the navigator knows that where the sun crosses the horizon is komohana, or west. He doesn't have to wait until sunset, however, to know which direction is west, since the moment he saw the sun rise in the east, he can instantly discern which direction is west by looking 180° behind him.

From these two directions he can then discern north as well as other points on the compass, and keep the canoe on the desired heading for reaching its destination.

It takes more than the sun, however, to keep a proper heading, and Polynesian navigators used this same technique with dozens of different stars.

Throughout the night, a navigator can watch a procession of stars as they appear on the eastern horizon— and correlate from their location which direction the canoe is facing and heading.

While the process in theory is simple enough (once you can recognize the stars), the constellations change with the boat's latitude in proximity to the equator. The navigator knows to adjust for these changes, and can also accommodate for unforeseen challenges such as clouds or stormy skies.

In addition to the stars, navigators will also use currents and wave patterns to deterring their direction and heading.

By feeling the rhythmic movement of the boat—rather than looking at the waves—a navigator can tell the direction from which a swell is rocking the boat. Since ocean swells follow seasonal patterns (see our weather page for more info), the navigator can use the rocking of the boat to determine the heading and direction of the boat in daytime or cloudy skies.

In fact, it’s been said that Master Polynesian navigators could close their eyes and discern five different swells all gently rocking the boat—and simply tell from a change in movement if their heading had drifted off course.

For more detailed info on Polynesian wayfinding, check out this page from the Polynesian Voyaging Society and prepare to be amazed.

Hokule'a: Sailing Into The Future

Finally, even though traditional Polynesian wayfinding is an art that's thousands of years old, it's still being used by navigators today to sail across the Pacific.

Though the art was definitely in danger of being lost (it took a man from Micronesia, Mau Piailug, to train Hawaiian navigators such as Nainoa Thompson in the traditional art of wayfinding), the craft has experienced a massive resurgence over the course of the last 30 years.

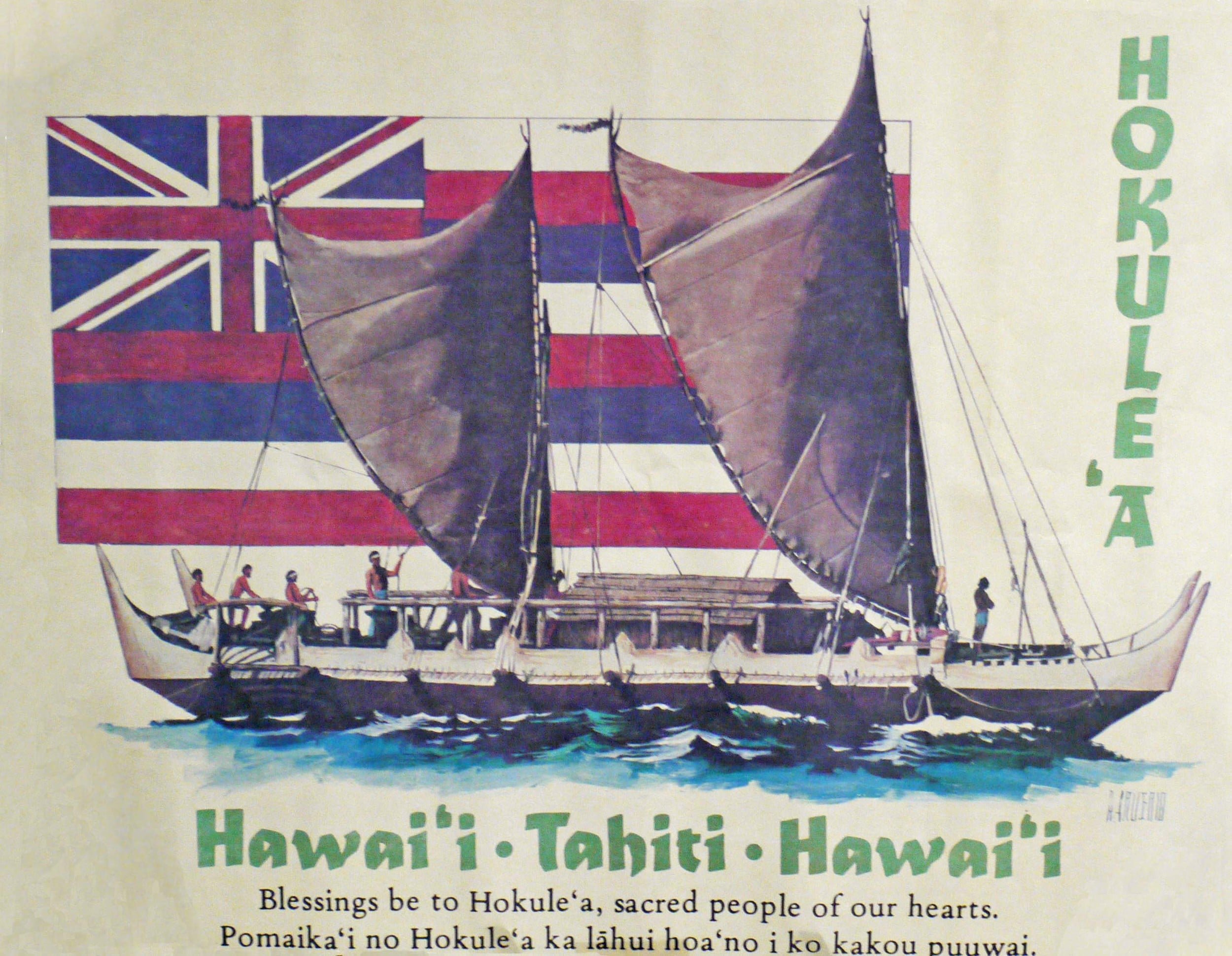

Here on Maui, organizations like Hui O Wa'a Kaulua are teaching our youth the traditional ways of Polynesian sailing and wayfinding. More prominent, however, is the story of Hokule'a, a traditional double-hulled voyaging canoe that in the past has undergone multi-year journeys of voyaging around the globe.

When Hokule'a launched in 1975—and a year later voyaged to Tahiti using only Polynesian wayfinding—it was the first time in approximately 800 years that a team of sailors traditionally navigated between the two islands by canoe.

When Hokule'a finally reached Tahiti, a crowd of over 10,000 people gathered on the shores to welcome home their Polynesian brethren who departed over 800 years prior.

It was a defining moment for the Hawaiian Renaissance and a resurgence of Polynesian culture, and the craft of celestial navigating and wayfinding is more alive than ever.